How to get there...

How to get there...

Metro: Bagatza. Leave the metro station by the G. Aresti street exit

Metro: Bagatza. Leave the metro station by the G. Aresti street exit

Step 1_ BARAKALDO. THE INDUSTRIAL LEADER

Route 1.3 km

Route 1.3 km

Start of the route: Gabriel Aresti street towards the river - San José street – Ferrerías street - Munibe street- Cervantes street

Barakaldo and Sestao were home to most of the heavy industry of Bizkaia, and during much of the twentieth century had the largest concentration of the iron and steel industry in Spain. These were factories that filled the river plain (where this route takes you), and the inland valley on the other side of the hills where both these towns are located.

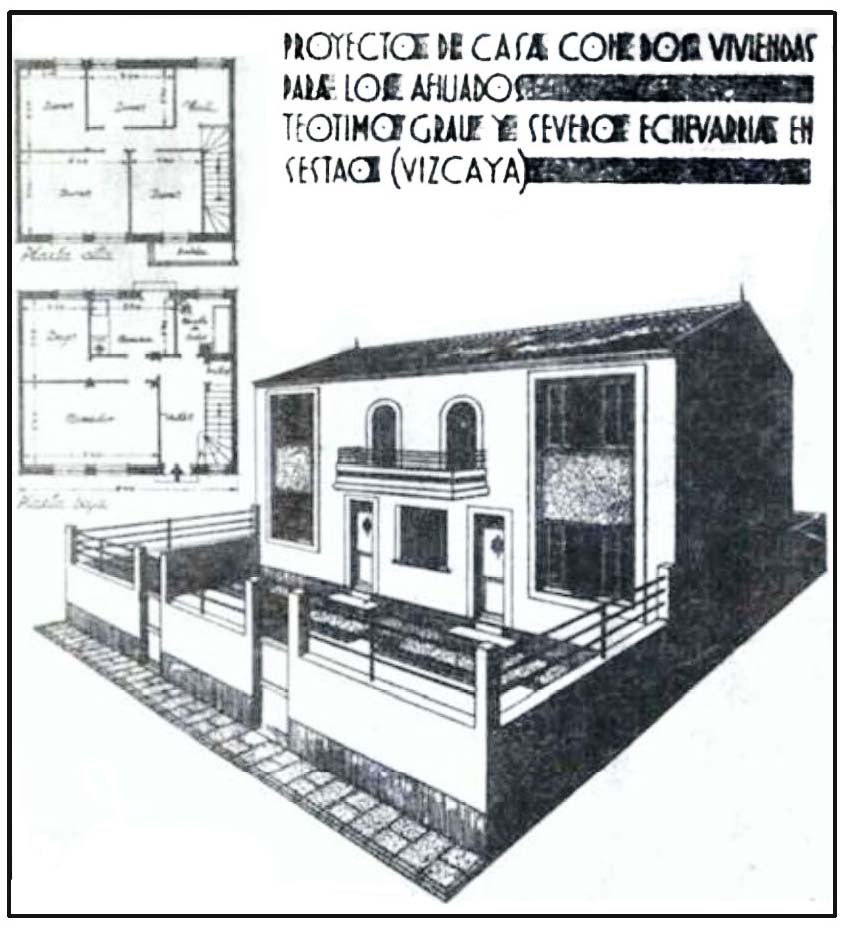

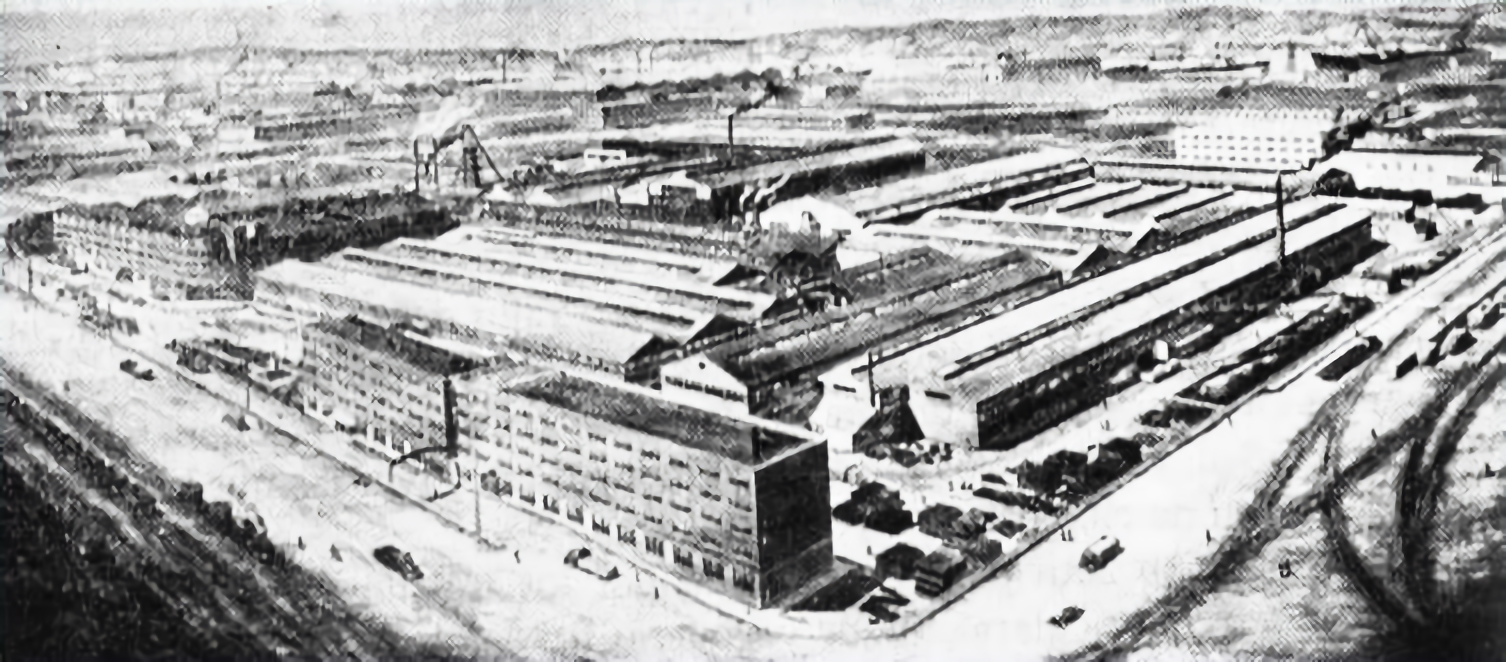

A reflection of this intensive industrial employment was the proliferation of residential groups that went under the name of "cheap houses". Both towns harbour almost 50% of all these houses in all Bizkaia, although many of these houses were replaced by buildings with higher density to accommodate the large influx of immigrants in the 1950s and 60s. In fact, along with the provincial capital, Bilbao, and Getxo with its palaces, these towns present the finest examples of residential and public architecture that arose out of industrialization.

A SUCCESSION OF "CHEAP HOUSES"

In the section that begins this route, you can see different types of this sort of social building, all designed by Ismael Gorostiza. At the corner of Gabriel Aresti, in the direction of the route, you see the group of houses called "El Ahorro" (1) in the street of the same name on the right; to the left, the houses of "La Felicidad", also with a ground floor and 3 upper floors.

At the next junction, "La Providencia" still has examples of semi-detached low-rise housing. Lower down, in Ferrerías street, there remains one of the finest groups: "La Tribu Moderna" (2), a residential group organized around courtyards of 4 houses with a small garden and a rear courtyard.

THE CHEAP HOUSES: HUMANIST ARCHITECTURE

The name does not refer to cost of the houses. It is a name of the laws enacted in the first third of the 20th century; these laws reflected the state aid given to promotions driven by workers' cooperatives or by the companies for their workers.

The types include all kinds of constructions: blocks of flats, terraced houses and detached houses. Their configuration, structure and level of finish were different depending on the income of the workers, technicians or employees.

These groups of houses, of which there are still over 50 throughout Bizkaia, followed similar proposals carried out in France and Britain, and reflected the three-pronged approach of the Hygienist movement in response to the overcrowding of the working classes; air, sunlight and water. They also provided solutions for companies and employees themselves to cope with the dark housing panorama in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries that decimated the quality and life expectancy of the workforce.

It was an initiative initially linked to companies and later to workers' cooperatives which contrasted to the lack of interest of the government in balancing population growth with housing developments for the working classes.

This was a situation that was compounded by the private sector in construction because rates of return in industry were much higher than those for investment in housing and they also had to contend with difficult terrain because the few flat spaces were absorbed by industry.

Even with the large number of housing promotions (57 in Bizkaia) that were set up, this failed to meet the residential needs of the huge numbers of workers who were attracted by the heat of industrialisation and, although the problem was reduced, there continued to be many homes with serious problems of hygiene, health and overcrowding.

More information (Spanish)

TOWARDS THE DESIERTO PLAIN

Munibe street continues and turns into Cervantes street, which runs down to the new park.

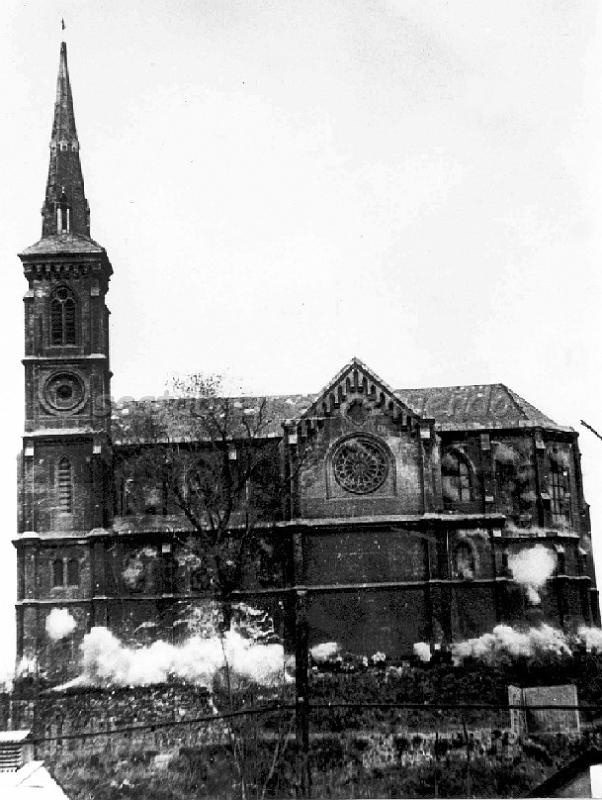

Before passing under the railway tracks, you can see in Murrieta street (3) a group of houses that illustrate the architectural richness of that time in Barakaldo. They are Modernist buildings, in a Viennese variant, dating from different phases between 1914 and 1924 and designed by the other great architect of the area: Santos Zunzunegui.

After crossing under the railway track, we arrive at what used to be the installations of AHV, an esplanade which is the extension of the "new" Barakaldo for residential, business and leisure purposes.

The first thing you can see is the new football pitch of Lasesarre (4), designed by Eduardo Arroyo and opened in 2003.

It replaces the old pitch located across the railway line, where there is a sports centre today and where for decades the fans of Barakaldo FC used to sit among the smells and smoke of the businesses in the area.

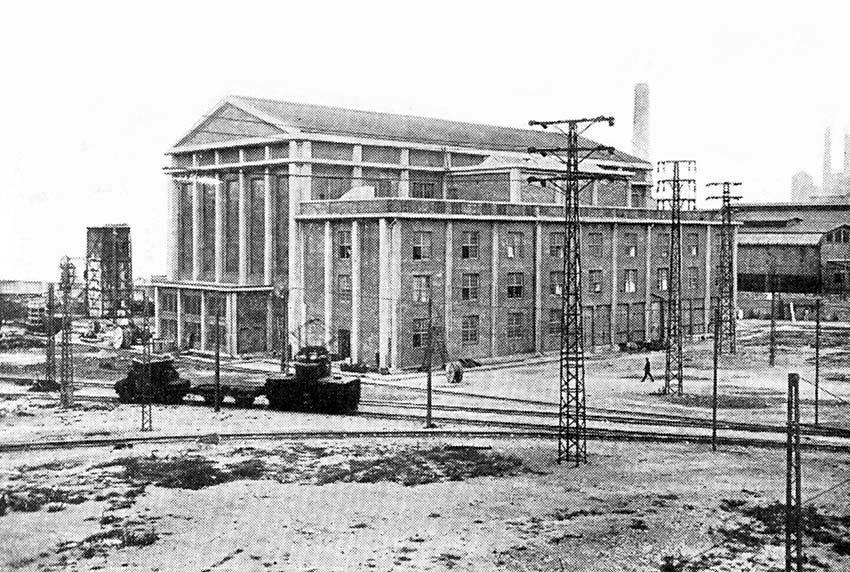

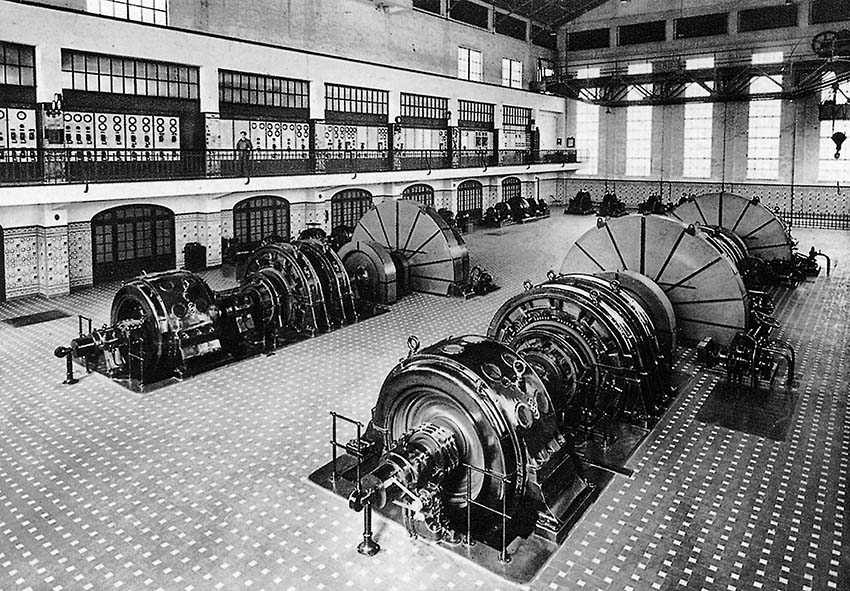

Moving towards the river Galindo we see on our right the "classical temple" called the Ilgner Building (5); from 1927 it housed the 2 generators that provided power for the rolling mills of Altos Hornos.

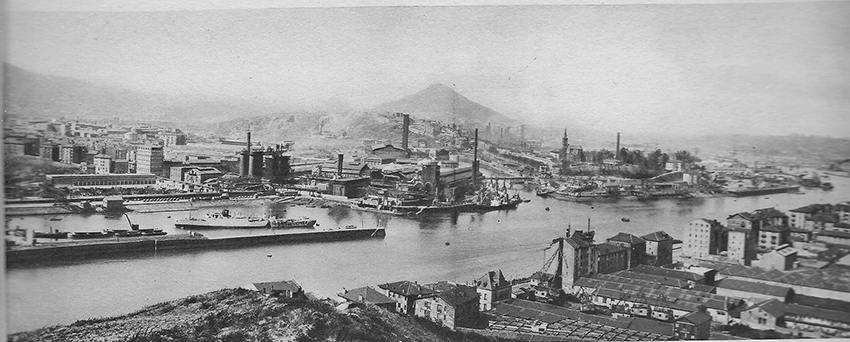

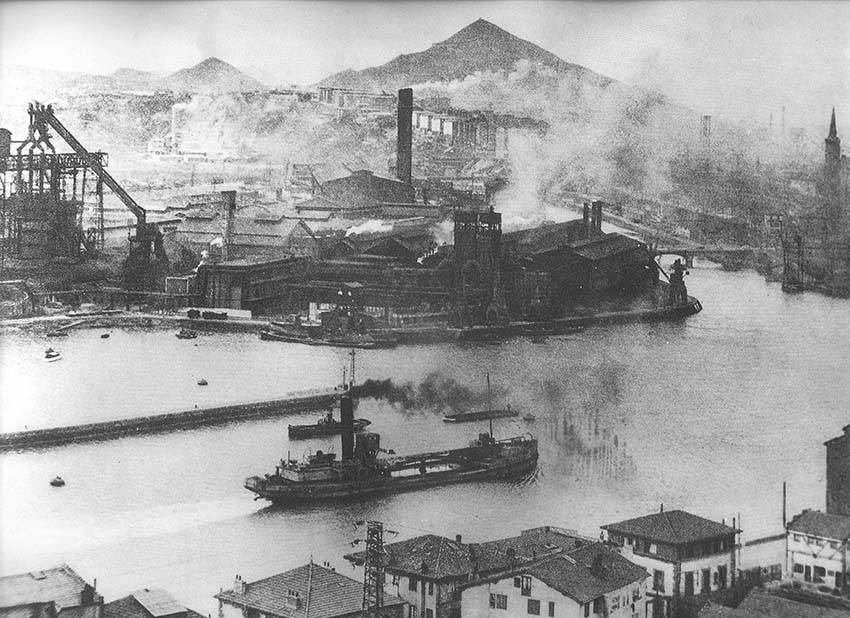

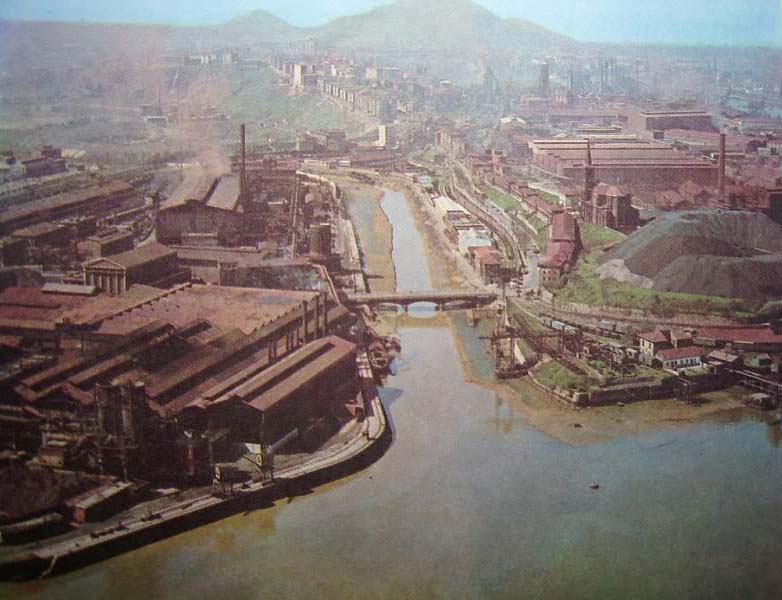

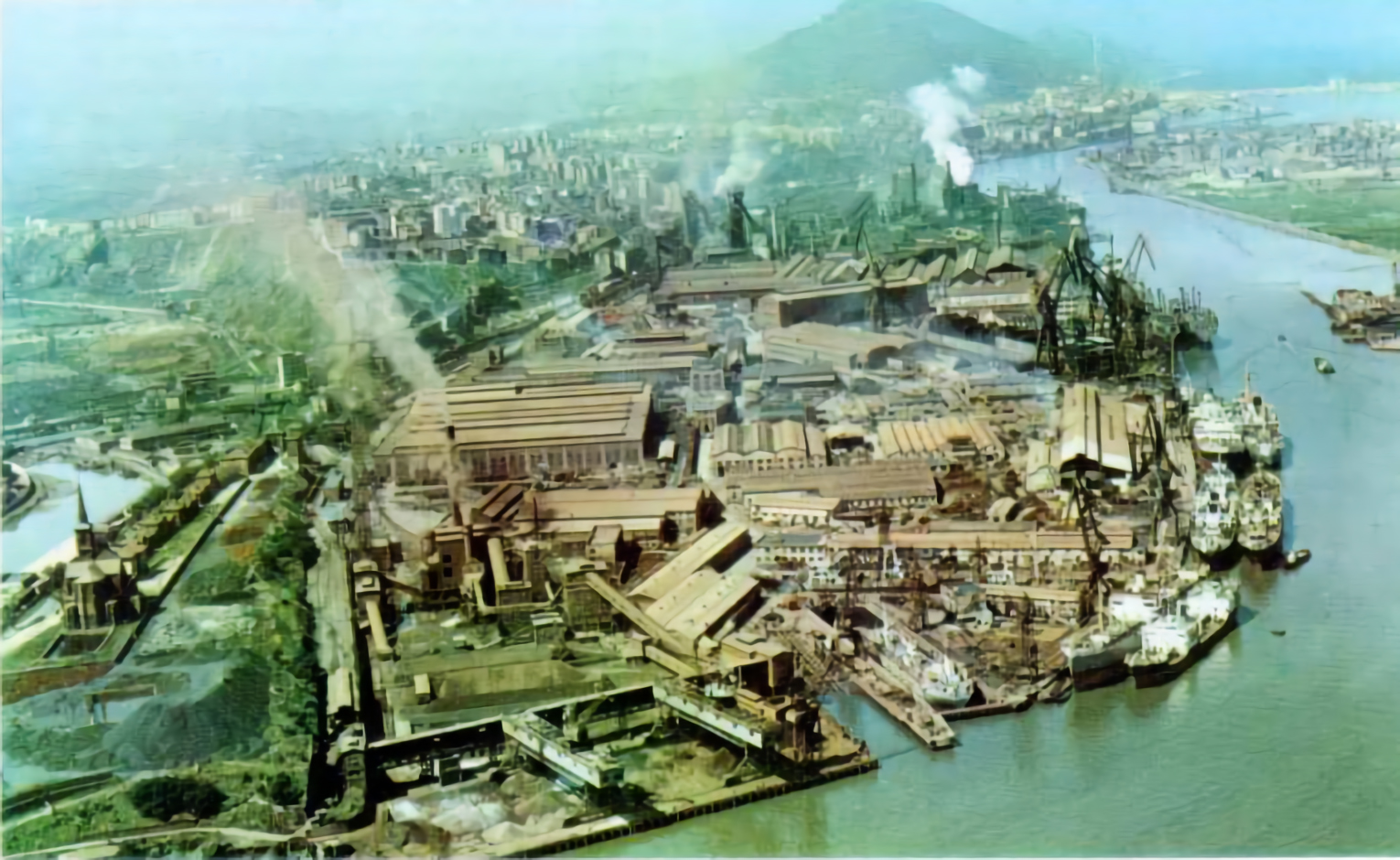

This area was for much of the 20th century the largest concentration of industry in the whole of Spain

It is noted for its rationalism in the use of reinforced concrete without any ornamentation, with walls pierced by long windows that help to create a feeling of lightness. Its textural quality is endorsed by the use of brick in the cladding.

After its rehabilitation in 1998, it now houses the headquarters of several new business initiatives, and one of the original generators has been preserved inside. It is one of the best examples of the conversion of an outstanding industrial building for new uses.

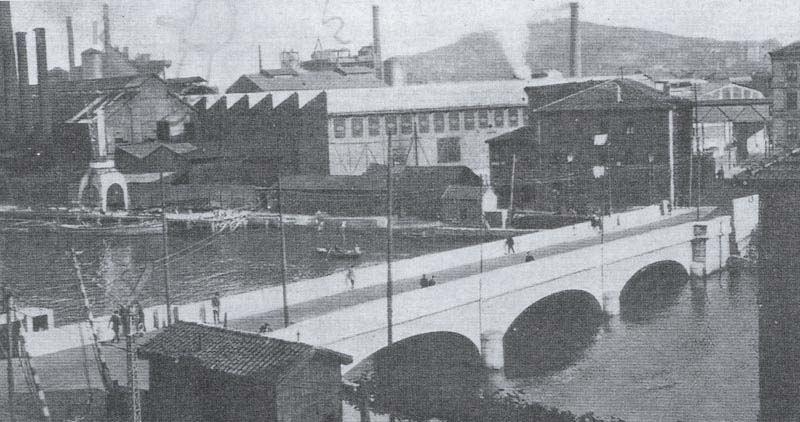

Opposite the Ilgner there are 2 bridges spanning the river Galindo; the town of Sestao is on the other side. This area is know as "La Punta".

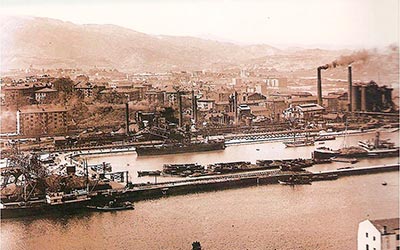

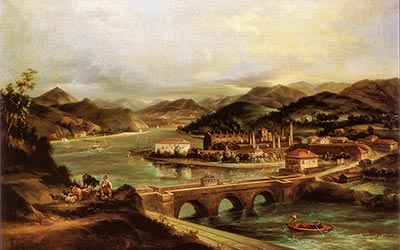

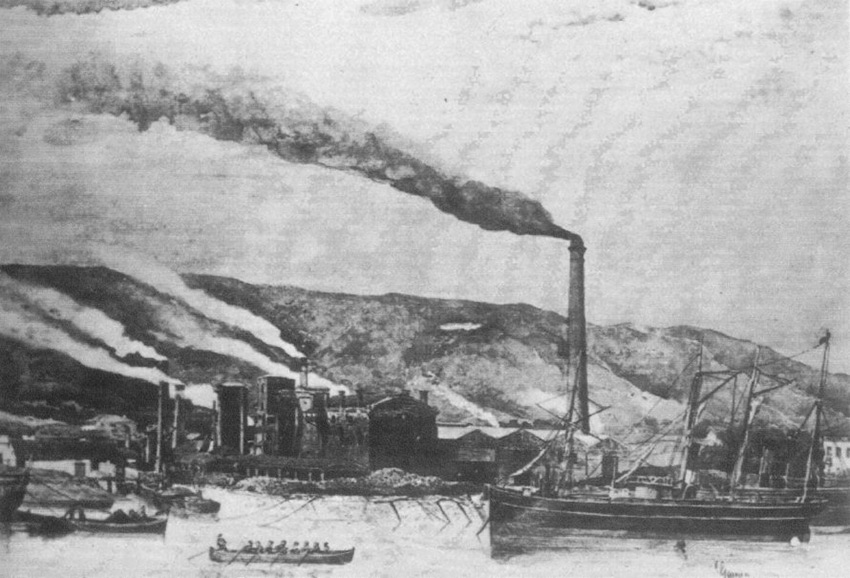

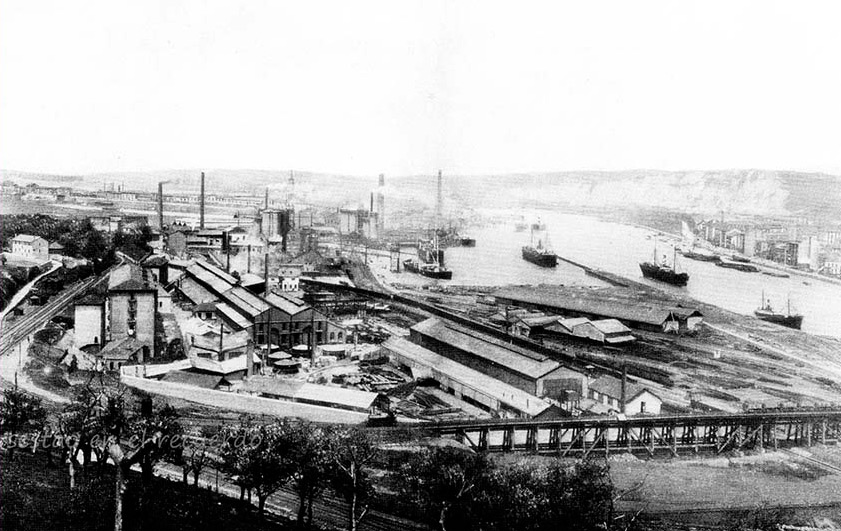

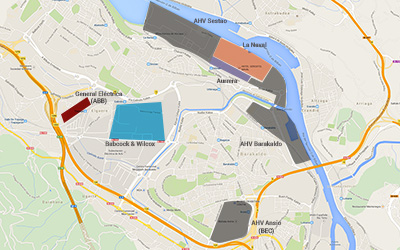

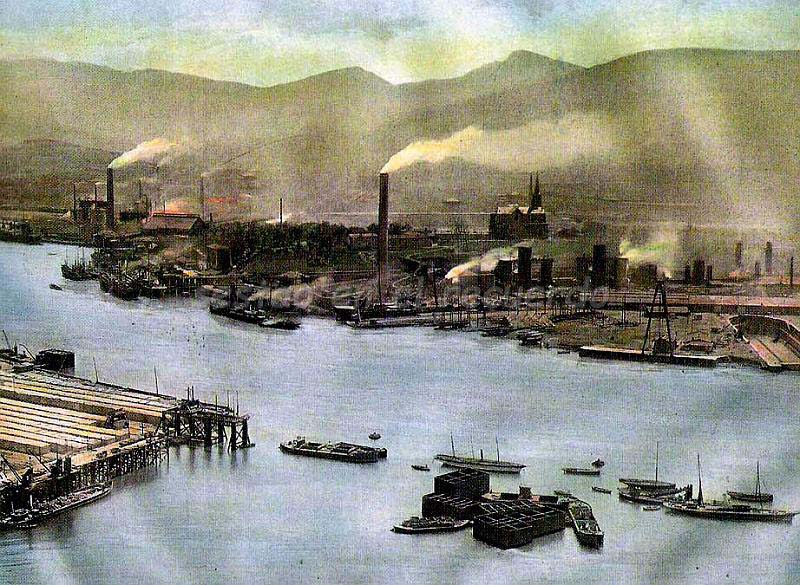

This meeting point of the river Galindo and the river Nervión was for much of the 20th century the largest concentration of industry in the whole of Spain. Behind you, on the side belonging to Barakaldo, was the steelworks Nuestra Señora del Carmen (1855), which became Altos Hornos de Bilbao in 1882. Along with the steelworks of La Vizcaya and La Iberia (both in Sestao), they would end up merging into the great company Altos Hornos de Vizcaya in 1902. Ahead, the whole of the bank of the Nervión on the Sestao side was a conglomeration of three large companies (the Aurrera foundry, the La Naval shipyard and AHV itself) with many workshops and auxiliary services around.

During the twentieth century, the river of Galindo and the Nervión itself were among the most polluted waterways in Europe. The enormous importance of this production area meant that, during the Civil War, the demolition of these iron and steel emporiums was mooted so that they would not fall into the hands of Franco's troops (1937). Finally, the Basque government of the time chose to leave them operating with the argument that its disappearance would bring more hardship to a population that was already in great need.

The effects of the disappearance or reduction of these industries make this part of the route both interesting and educational and also aesthetically hard. We are in a region with the highest rates of unemployment in the Basque Country, and Sestao has the highest rate (18%) with a population loss of 30% since the end of the great companies around it during the 1980s and 1990s.

The town is located high on a hill, surrounded by the river Nervión Valley (where we are now) and the course of the river Galindo on the other side.

Both valleys were the site of large companies including Altos Hornos de Bizkaia, Babcock&Wilcox, General Eléctrica, La Naval and Aurrera which employed about 40,000 people in the 1970s. Today because of closures or a drastic reduction in the workforce (as in the case of La Naval or the new Acería Compacta compact steelworks), and even with the recent opening of new companies, only about 2,000 jobs have remained.

This part of the route passes through the area most directly linked to the now-defunct Altos Hornos and, after the effort made in Barakaldo, the regeneration process for Sestao is in full implementation, with a plan to redevelop derelict premises and land, restore houses that have deteriorated over time, boost trade and services, and so on.